Our voting

We voted at 8,277 shareholder meetings and on a total of 90,449 proposals in the first half of 2024.1 Our voting disclosure is continuously updated on our website. In this review, we look at trends and outcomes, including on key topics such as board composition and executive pay. We discuss how sustainability issues are reflected in our voting, including how we are pushing for progress on climate risk mitigation.

Our general approach is to support the proposals supported by the board, on the basis that we participate in electing the board and entrust it with running the company.

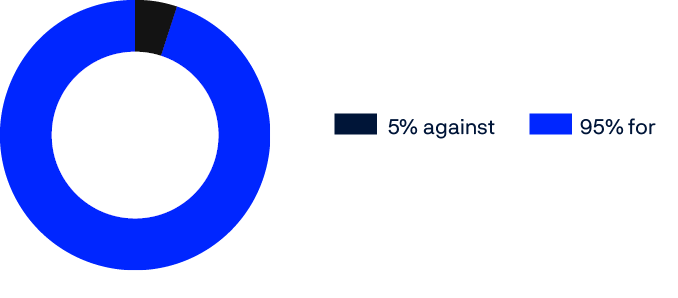

This year, we voted against the board’s recommendation on 5 percent of proposals and voted against at least one proposal at one third of company meetings. Concerns about board independence and the combination of chair and CEO roles continued to drive many of our votes against companies. We voted against around one in ten CEO pay packages, including in the US where we continued to apply a stricter voting assessment to the largest packages to identify the pay structures we view as most problematic and misaligned with long-term value creation. We held more boards to account for material failures in the oversight, management or disclosure of sustainability risks. Meanwhile, the number of shareholder proposals on environmental and social topics continued to rise in the US, sparking debate about proposal oversight by the US regulator and potential risks to shareholder rights. We filed our own climate-related shareholder proposals, in line with our 2025 Climate action plan and our Climate change expectations of companies.

1 Unless otherwise stated, all references to voting patterns in other years also refer to the period from January to June, for comparative purposes.

Our approach to voting

Through responsible investment practices, we seek to increase the return and reduce the risk of the fund’s investments. As an active owner, we engage in discussions with the management and boards of our portfolio companies to better understand and potentially seek to improve aspects of governance, including of material environmental and social matters, as well as overall strategy and performance.

Our ownership gives us the right to vote at shareholder meetings on matters such as the election of board members, how executives are paid, aspects of capital structure, as well as on topics proposed by shareholders.

We may vote against certain proposals, including the election of directors, where we consider that the board is not able to operate effectively, that our rights as a shareholder are not adequately protected, or that the company’s practices are materially misaligned with the principles expressed in our global voting guidelines. We may also vote in favour of well-crafted proposals on material matters put forward by shareholders. Such proposals are not supported by the board and management. We consider these individually against our decision framework.

Our voting guidelines are based on internationally recognised standards, such as the G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance, UN Global Compact, UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, and OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. They are also informed by the principles that we have expressed through our position papers on various governance topics, our expectations of companies on material sustainability issues, and our 2025 Climate action plan.

Our positions and expectations reflect the good practices that we wish to see companies adopt over time to reduce risks and increase value. We advocate these practices in our dialogues with companies. Through our voting, we aim to address those companies most misaligned with these positions and expectations, and move them towards these standards over time. Accordingly, our voting guidelines may include lower thresholds than our global positions or expectations in certain areas, with the intention of raising them in the future.

We aim to be consistent and predictable in our voting decisions, so that they can be anticipated by investee companies and explained by our voting guidelines and other documentation. To support this, since 2021, we publish our voting intentions five days before each meeting, with a brief rationale referring to the relevant part of our voting guidelines whenever we vote against the board’s recommendations. In 2024, we began disclosing expanded voting rationales for selected votes, to provide additional transparency.

Being consistent and predictable does not mean that we vote the same way every year on every issue, or even at every company. When applying our voting guidelines, we consider local market context and, where possible, company-specific circumstances, including insights from our portfolio managers where we have a significant active holding in a company. Our internal portfolio managers have deep, company-specific knowledge, which is a valuable resource when we vote. In 2024, portfolio managers participated in voting decisions for 567 companies, representing 56 percent of the value of our equity portfolio.

How we voted in 2024

We continued to support management and vote in line with the board’s recommendation in most cases, but we voted against management on at least one proposal at around one third of meetings. This is similar to previous years.

We support management in the majority of cases

Boards and shareholder proposals where we voted against the board’s recommendation.

Meetings in which we voted against the board's recommendation on at least one proposal.

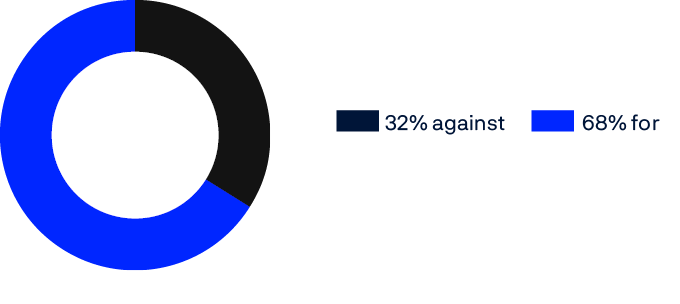

Some of the reasons2 we voted against were:

Board independence

One of the most common reasons we voted against directors was insufficient levels of board independence. Although we have seen improvements in independence levels globally, this only led to a slight decrease in the number of companies we voted against, from 7 percent in 2023 to 6 percent in 2024. For further information, see the section on board composition and effectiveness.

Combined chair/CEO roles

We continue to have concerns about the roles of chair and CEO being held by the same person. Around 80 percent of the companies we voted against for this reason are in the US and South Korea, where this structure remains relatively prevalent. For more information, see the section on board composition and effectiveness.

CEO pay

We have long advocated for companies to adopt simple pay packages for their CEOs based on long-term share ownership. Our voting policy aims to capture those companies most misaligned with our principles. This year, we voted against approximately one in ten CEO pay packages. Overall, we voted against at least one proposal – including director elections – at nearly 5 percent of all companies we voted on based on concerns about CEO pay. The most common concerns were the use of one-off awards such as ‘golden hellos’, awards that are paid out over too short a timeframe, or instances where we considered the board had not taken sufficient steps to respond to concerns from shareholders regarding pay in previous years. We continued to apply a stricter assessment to the largest pay packages globally, leading us to vote against CEO pay at 93 companies in 2024, compared to 102 in 2023, where we assessed the package to be unduly costly and where we had significant concerns about its structure. For more information, see the section on the CEO pay.

Holding the board accountable

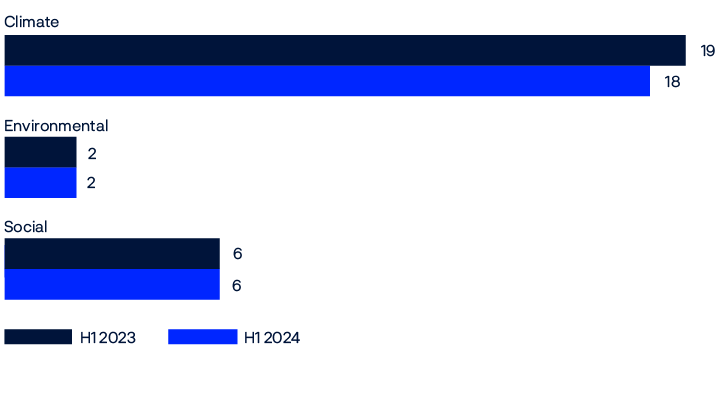

In a small but important number of cases, we vote against board members where we believe they have failed to fulfil their duties. In the majority of cases, 107 companies in 2024, this is related to governance concerns. Examples include situations where a company received low support for a pay proposal and we determined the board failed to adequately address the issue, or where a company experienced material failures of governance, risk oversight or disclosure, or a breach of fiduciary responsibilities. In recent years, we have expanded this to consider environmental and social factors, voting against directors where we consider there to be material failures in the oversight, management or disclosure of climate risks (18 companies in 2024), social risks (6 companies in 2024) or other sustainability risks (2 companies in 2024). The decision to vote against typically follows engagement with the company where we have not been satisfied with the company’s response.

Board gender diversity

Our global expectation is for each gender to represent at least 30 percent of the board, which we will implement in our voting guidelines over time. This year, we strengthened our guidelines to require at least two representatives of each gender in most developed markets, and at least one in most emerging markets. We were encouraged to see more companies in developed markets meeting this minimum threshold this year, although there is still progress to be made. For more information, see the section on board composition and effectiveness.

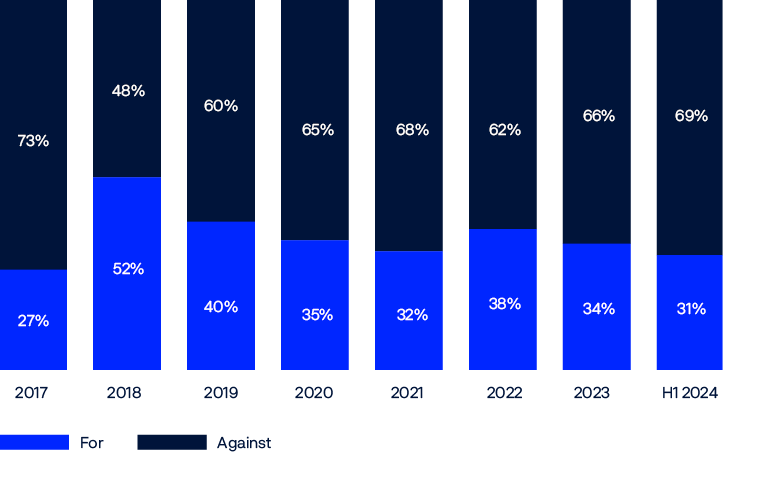

Around 3 percent of the proposals we voted on were shareholder proposals, which we assess on a case-by-case basis. After careful consideration, we supported 48 percent of shareholder proposals in total, 52 percent of those relating to governance and 31 percent of those on sustainability topics. For more information, see the section on shareholder proposals.

Concern leading us to vote against in 2024

The percentage of all companies we voted against driven by concerns on selected topics

US shareholder rights

The rise in shareholder proposals being filed at US companies has prompted debate about how the US Securities and Exchange Commission oversees such proposals and led Exxon Mobil to file a lawsuit against shareholders related to the submission of a shareholder proposal. After engagement with the company’s management and board, we voted against the lead independent director due to our concerns around the potential impacts of litigation against shareholders stemming from the submission of a shareholder proposal. This decision reflects our continued commitment to the protection of shareholder rights.

2 See the appendix for a full breakdown of the reasons we voted against companies and how many companies we opposed.

Board composition and effectiveness

We generally own a relatively small percentage of the companies in which we invest, and we delegate most decisions to their boards and management teams. Voting to elect directors to the board of a company is therefore, one of our most important shareholder rights, with director elections accounting for nearly four in ten of the resolutions we vote on.

We expect board members to act independently and without conflicts of interest, to have the right balance of experience and skills to carry out their duties, and to be accountable for their decisions.3

Voting on alternative board candidates

In recent years, the Walt Disney company has faced strategic challenges, pressuring its stock price performance, as well as leadership turbulence and uncertainty, after an unsuccessful CEO transition required a return of its former long-tenured CEO. We regularly engage with Disney at board and management level, as we seek to do with all of our largest holdings. These discussions, which involve our portfolio and stewardship managers, help us understand the company and board better and to share our views and investment perspectives. We value these interactions, including those with the chair and leading board members, and believe they help us to make better investment and voting decisions.

At the 2024 AGM, we considered whether and how concerns over strategy and CEO succession should be reflected in our vote, including whether we should support alternative board candidates proposed by another shareholder, in place of the incumbent directors.

After carefully considering the case made by the proponent and our continuous dialogue with the incumbent board, we concluded that we would not support the alternative candidates. However, we found there was reason to hold the board to account and therefore voted against the chair.

Board independence

We view board independence as a core component of good governance. To balance competing demands, a board needs a sufficient level of independence and objectivity to be better equipped to guide strategy, oversee management and be accountable to shareholders. In most markets, we expect at least half of board members to be independent, with some exceptions based on market context.

Overall, we are seeing continued improvements to levels of board independence in developed and emerging markets. We voted against 20 percent fewer directors or other relevant proposals than in 2023 on the grounds of independence. This includes in Japan, where improvements to levels of board independence led us to vote against 27 percent fewer proposals than in 2023.

Separation of the roles of chair and CEO

One of the biggest drivers of our votes against companies was due to the roles of chair and CEO being held by the same person. We have long advocated for the separation of chair and CEO and believe that a non-executive chair is in a stronger position to guide strategy, oversee management and promote the interests of shareholders.

The US is one of the markets where a combined role remains common. This concern contributed to us opposing the chair/CEO at 311 companies (around 20 percent of the US companies where we voted), down slightly from 317 companies in 2023, reflecting relatively slow change on this issue.

We will continue to advocate for our portfolio companies to elect an independent chair, and expect them to clearly demonstrate how any conflicts of interest are being mitigated in cases where separation is not considered to be feasible in the near term.

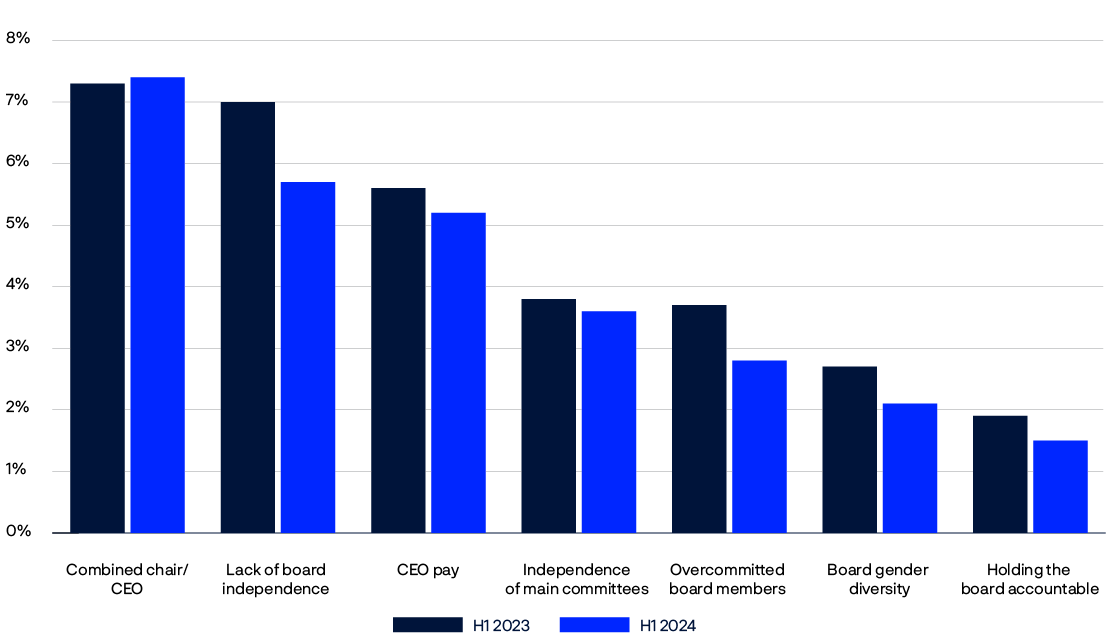

Board gender diversity

In the context of wanting effective boards with the diversity of skills, experience and perspectives necessary to fulfil their duties, we view having sufficient representation of each gender as an important indicator of board quality and decision-making.

Despite some progress,4 supported by regulatory and voluntary minimum standards for the inclusion of women in various markets,5 women continue to be under-represented on company boards.

Our expectation is that each gender represents at least 30 percent of the board. We are implementing this progressively in our voting guidelines and will vote against boards that do not meet minimum thresholds. We also discuss this issue in our dialogues with boards and ask those that have not yet achieved 30 percent representation of both genders to consider setting time-bound targets to do so.

We saw progress in many developed markets in 2024. In developed markets where we expect at least two representatives of each gender, 91 percent of companies met this threshold. In emerging markets where we introduced a new guideline of at least one representative of each gender, we were encouraged to see that 92 percent of companies met this threshold.

Recognising that the dynamics that influence the representation of women on boards are heavily impacted by local market context, we continue to make exceptions in certain markets. This includes certain developed markets, namely Japan, Singapore, South Korea and Poland, which have seen slower progress on board gender diversity. In these markets, we introduced a guideline requiring at least one representative of each gender and were encouraged to see that 78 percent of companies met this initial threshold.

Our guidelines for all markets are continually under review, with the aim of moving towards our expectation of 30 percent representation of each gender in due course. As of 2024, 65 percent of boards across our portfolio (58 percent in developed markets and 80 percent in emerging markets) do not yet meet our expectation of 30 percent, highlighting the progress yet to be made.

Average percentage of women on boards in our portfolio

The average percentage of women on boards in our portfolio per market classification

3 See our position papers on board diversity, board independence, time commitment of board members and separation of chairperson and CEO.

4 The percentage of female board members at MSCI ACWI Index companies increased from 17.9 percent to 25.8 percent between 2018 and 2023, https://www.msci.com/documents/1296102/43943104/MSCI+Women+on+Boards+and+Beyond+2023+Progress+Report.pdf.

5 For example, the 2022 European Directive requires EU-listed companies to have either 40 percent representation among non-executive board members or 33 percent representation of each gender among all board members by 2026.

CEO pay

How a company’s management team are incentivised and rewarded can have a significant influence over their decision-making and performance over time. It is particularly important in the case of the CEO. We advocate simpler pay structures based on CEOs building up and holding shares for the long-term. We believe this most effectively aligns their interests with our own as a long term shareholder. It also reduces the risk of unintended consequences of basing a significant portion of pay on achieving various performance metrics, given the difficulty in finding ones that sufficiently drive long-term outcomes.

Currently, relatively few companies around the world use simple structures of the kind we advocate for. Many use a combination of a cash salary and short- and long-term incentive schemes, paid partly in cash and partly in shares which are released to executives on the basis of complex multi-year criteria.

We do not think it would be constructive for us to oppose the majority of CEO pay packages on the basis that they do not yet follow our preferred model. We therefore take a pragmatic approach in our voting guidelines, setting various limits that aim to identify the packages most materially misaligned with our preferred approach. For example, we will not support any pay packages that award CEOs shares over a timeframe that we consider to be too short-term, or which include the use of substantial one-off awards such as ‘golden hellos’ and severance payments. We will also vote against packages which appear unduly costly and where we have concerns about their overall design of pay schemes or their alignment with performance. Finally, we consider whether boards have appropriately responded to shareholder concerns about pay in previous years.

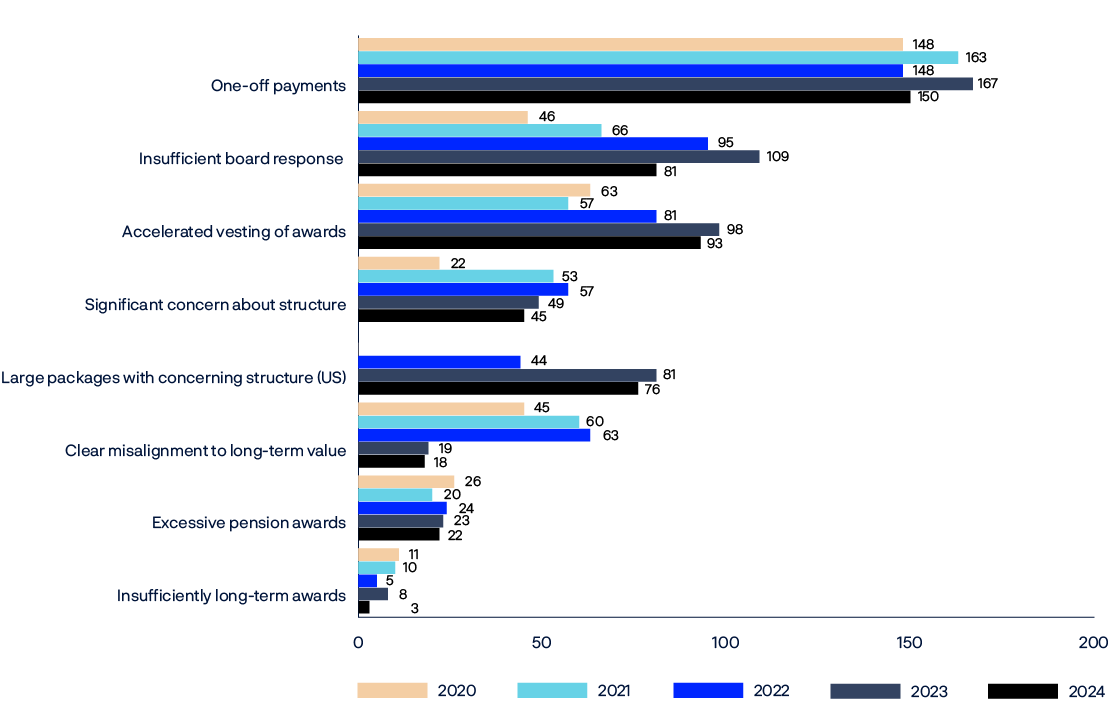

In the first half of 2024, we voted against a total of 314 pay packages globally, compared to 345 in 2023. The US market accounted for roughly 37 percent of votes against executive pay plans, down from 41 percent in 2023.

The use of one-off awards continues to be the largest driver of our votes against CEO pay, while we saw a decline in cases where we voted against pay packages for a lack of responsiveness to shareholder concerns about pay. Overall, our voting on CEO pay has remained fairly consistent year-over-year.

Reasons why we voted against CEO pay from H1 2020 – H1 2024

US CEO pay

In the US, where CEO pay levels are among the highest in the world, the philosophy of ‘pay for performance’ continues to dominate the way in which packages are designed.

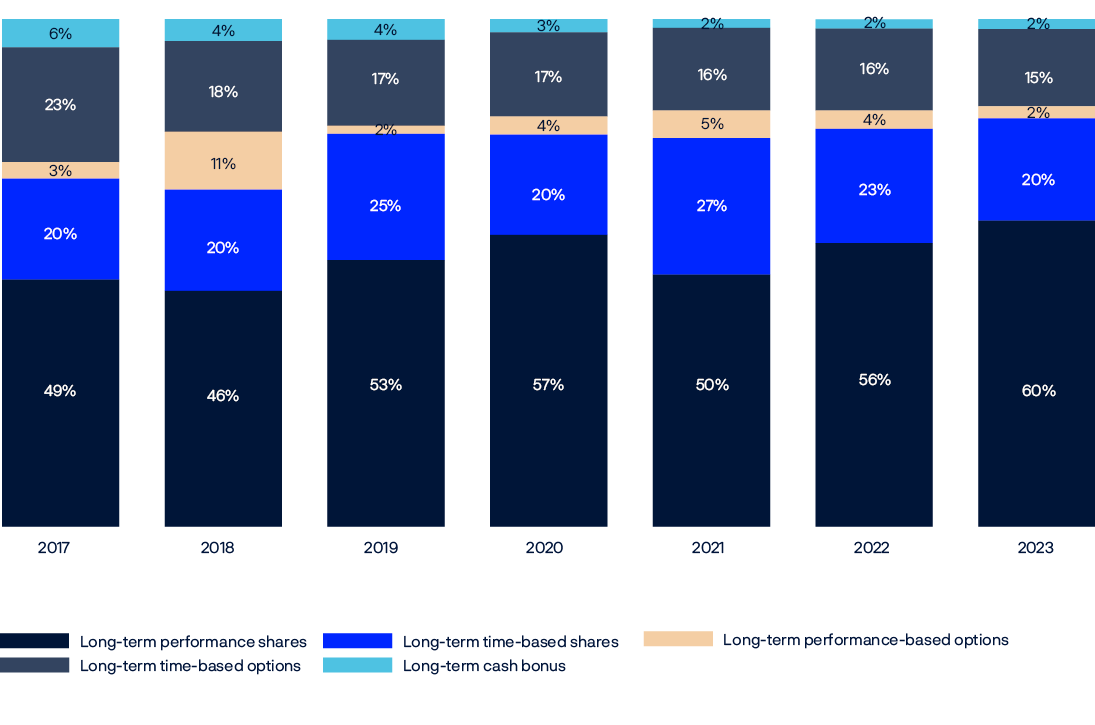

This means that the majority of a typical CEO’s pay is earned through short- and long-term incentive plans. The long-term plans typically make up the biggest portion of pay, and the largest – and growing – component of these plans is performance shares: shares the CEO earns if certain performance conditions are met over a set period of time.

Long-term performance shares make up a growing portion of US CEO pay.

Breakdown of proportion of different components in disclosed long-term pay for US S&P 500 CEOs, Norges Bank Investment Management holdings fiscal years 2017 – 2023. Note that packages typically include cash salary and short-term incentives in addition to these. Note: we removed Tesla from the dataset due to an abnormally large options grant in 2018 which is not reflective of US trends and which significantly distorts the data.

This approach seems intuitive: CEOs should only be paid if they perform, and long-term performance is better. However, in practice, we find that ‘long-term’ ‘performance-based’ packages often do not deliver as intended, for a number of reasons:

- Performance pay does not always correlate with the shareholder experience. Research has found that incentive plans using ‘performance shares’ seem to cost more and be associated with weaker stock performance1.

- Defining the right measures of ‘performance’ is often complex and flawed. CEOs may achieve targets in ways misaligned with long-term value creation or be rewarded for factors outside their control. Boards may select metrics that are not material for long-term value, or calibrate targets so that a certain portion of the award is very likely to pay out.

- Long-term plans are, in fact, not very long-term. In the US, the overwhelming majority of pay awards pay out in three years or less, which is far shorter than the five-to-ten-year horizon that we consider appropriate.

- Incentive plans add complexity to CEO pay packages that can distract CEOs, boards and shareholders from a company’s strategic aims and hinder transparency.

We continue to advocate a change in approach to CEO pay in the US, at both company and market level. We also continue to apply a stricter voting assessment to the largest US CEO packages – which we currently define as those worth 20 million dollars or more – and oppose those with structures we consider most problematic and misaligned with long-term value. This led us to vote against 76 packages above this level in 2024, broadly in line with 2023.

6 Hodak, M. (2019). Are Performance Shares Shareholder Friendly? Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 31, 126-130.

Environmental and social topics

We aim to promote long-term value creation at the companies we invest in and to minimise negative effects on the environment and society. We have an ongoing dialogue with portfolio companies on material environmental and social risks, and this includes conveying our expectations on core topics such as climate change and human rights.

This is reflected in our voting in several ways. First, we hold boards to account for material failings in the oversight, management or disclosure of environmental, social or climate risks. Second, we vote on and selectively file shareholder proposals covering a wide range of environmental, social and governance topics.

Holding boards to account for sustainability risks

We believe that boards are accountable, in their oversight role, for ensuring that companies manage material sustainability risks in their business planning and do not contribute to unacceptable environmental or social outcomes. Where we judge there to have been a material failure in a company’s oversight, management or disclosure of environmental, social or climate risks, we may vote against directors.

Before voting against a company on sustainability-related matters, we will seek to engage with them to better understand their practices and to ensure they understand and meet our expectations. We consider voting against directors to be a point of escalation when engagement outcomes or very specific events are unsatisfactory.

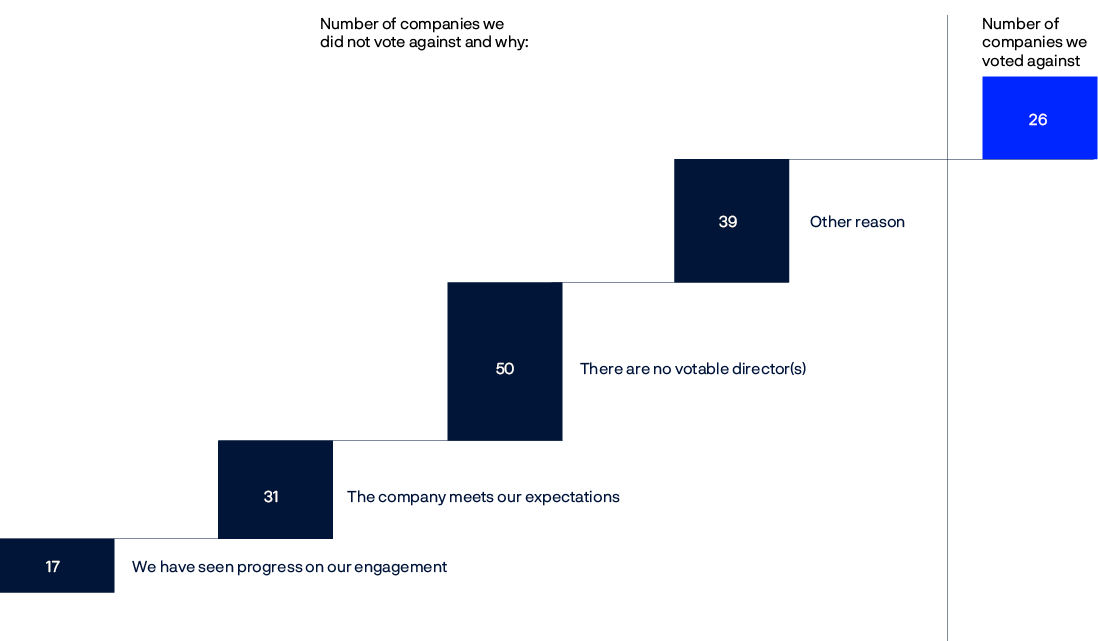

In 2024, we identified 152 companies as having heightened risks of sustainability failings. In these cases, we evaluated whether to hold board members to account by voting against them. We considered factors such as the company's responsiveness to engagement, what we had learned from such interactions, any improvements made over time, and forward-looking commitments.

Following this assessment, we voted against 26 companies, compared to 27 in 2023.

Our votes against boards for sustainability failings

Our assessments on board accountability in 2024

Accountability on tax

In 2024, for the first time, we voted against a director at one company where the company’s disclosure around tax governance, associated risk management frameworks or overall approach to tax was insufficient, and engagement had not proven productive. We view responsible tax behaviour as an important component of responsible business conduct and, as a financial investor, have an interest in companies' tax practices having appropriate board oversight and being supportive of long-term value creation.

Shareholder proposals on sustainability

We believe shareholder proposals can be a useful tool in cases where a company lags market standards, where disclosures are lacking, where we have concerns about specific company strategies, or where a proposal aligns with our positions or expectations and we do not believe a company is taking sufficient action to meet them.

We may also file or co-file shareholder proposals in selected cases, for example where we do not believe a company has responded sufficiently to our engagement dialogue on an issue material to long-term value.

Shareholder proposals are used in various markets around the world but most significantly in the US, where 75 percent of environmental and social shareholder proposals and 14 percent of governance shareholder proposals are filed.

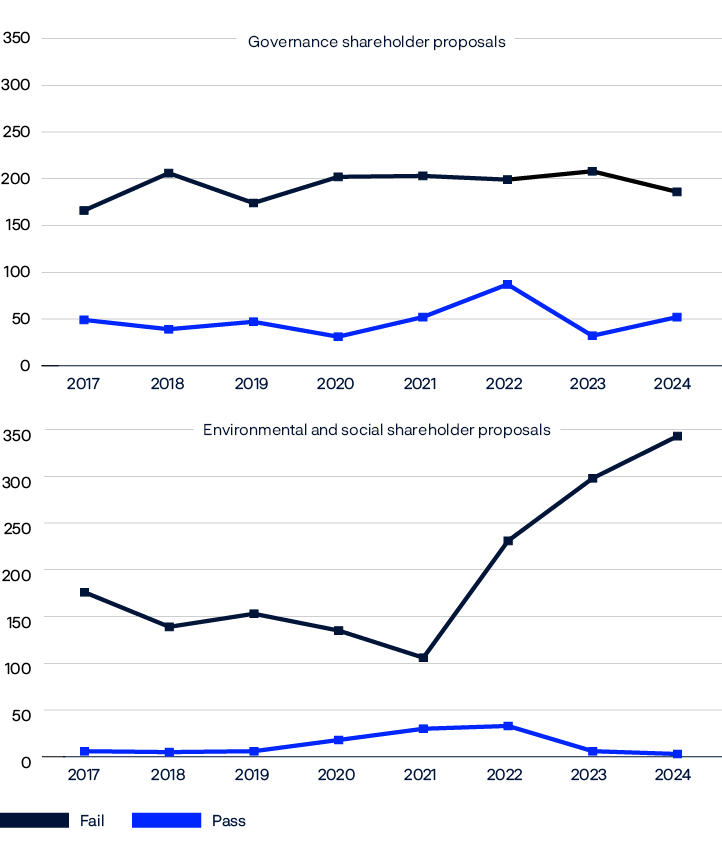

Number of shareholder proposals that passed and failed in the United States

In recent years, we have seen a rising number of shareholder proposals on environmental and social topics in the US, but declining support from investors, against a backdrop of increasing politicisation of ESG topics. Support for governance-related shareholder proposals has been more consistent.

These shareholder proposals often ask for transparency and action on environmental and social topics that shareholders deem material for the company. Certain issues appear frequently since they are relevant for a wide range of industries, such as reporting on climate change strategies and emissions, maintaining an inclusive and tolerant work environment, and being transparent about political activities.

Overall, we supported roughly the same proportion of shareholder proposals on sustainability topics in 2024 as we did in 2023.

Our level of support over the years

Our thinking on…

Frequent topics for environmental and social shareholder proposals

We see a range of environmental and social issues appearing on the ballot via shareholder proposals. In these boxes, we share our views on some of those appearing frequently in 2024.

Our thinking on…

Corporate policy engagement

Shareholders are increasingly calling for companies to disclose how they govern their public policy activities, including their lobbying and political expenditures. To help companies understand where we stand on this issue, we recently published a view which discusses how we think companies should engage responsibly in public policy activities.

Our thinking on…

Biodiversity and ecosystems

With clear scientific evidence that natural ecosystems and the biodiversity that underpins them are rapidly declining, the risk to our investments is undeniable. Along with other shareholders, we are calling on our portfolio companies that depend or have an impact on ecosystems and biodiversity to incorporate nature-related considerations into their corporate strategy, risk management and reporting. Further discussion can be found in our paper on this topic.

Our thinking on…

Animal welfare

Over the past decade, we have seen companies increasingly acknowledge animal welfare standards. However, their approaches and commitment levels vary significantly. Farm animal welfare, particularly concerning pigs and chickens, has emerged as a relevant topic during our stakeholder discussions, and we note that a number of shareholder proposals have been filed on this topic at US consumer companies each year. Although we do not have explicit expectations in this area, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises were updated in 2023 to make animal welfare part of responsible business conduct. On this basis, animal welfare is integrated into our responsible investment work, including the fund’s ethical guidelines, consumer interest expectations, biodiversity and ecosystems expectations, and voting practices.

Our thinking on…

Labour rights

The commitments that companies make to the right to freedom of association and collective bargaining have come under increasing scrutiny. Labour rights are an essential component of human rights, and that an efficient human capital management strategy encompasses robust labour relations. When we assess proposals on the topic, we consider the commitments companies have made and what steps they have taken to meet them, in addition to assessing the proposal’s materiality, scope and prescriptiveness.

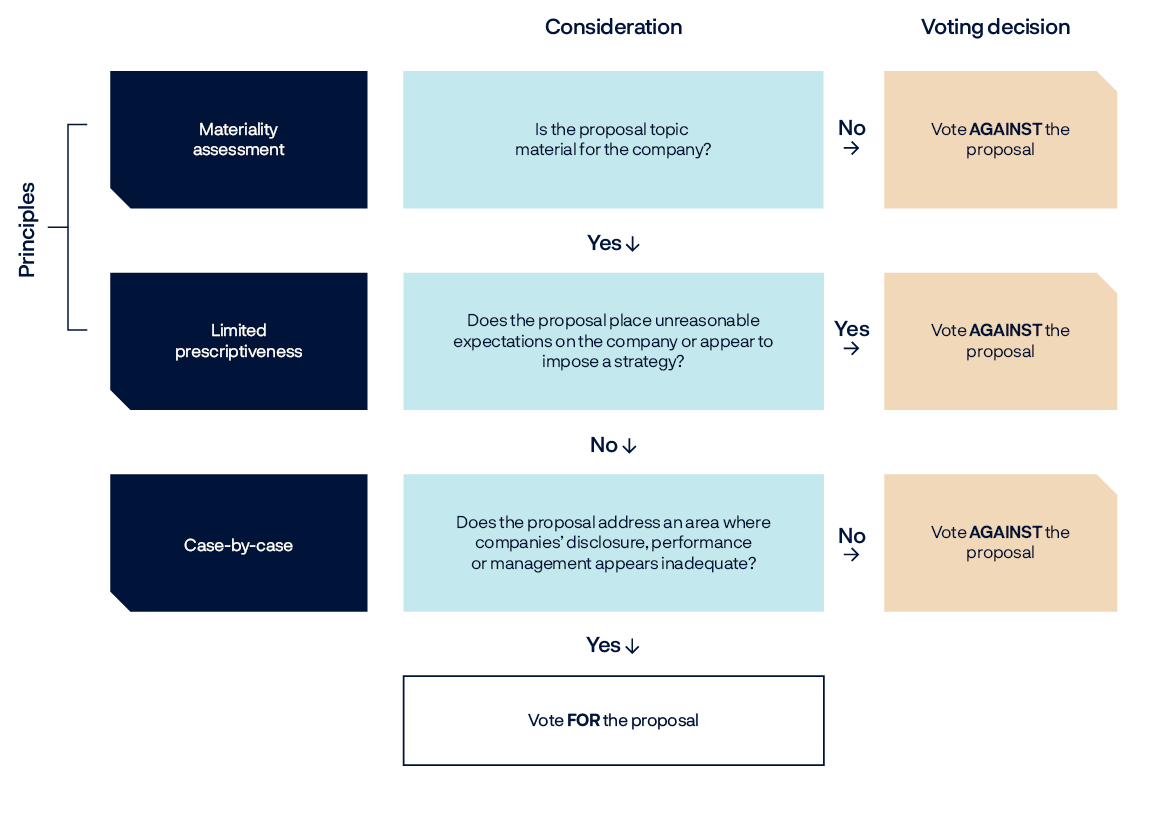

We evaluate each shareholder proposal individually, drawing on our in-house expertise on governance, environmental and social topics, as well as current research and market trends, to reach an informed voting decision. We follow a three-stage framework in reaching our decision, first considering the materiality, then the prescriptiveness of the proposal, and finally the scope, including an assessment tangible company actions on the topic. This is discussed further in our responsible investment report and in our paper on sustainability shareholder proposals.

Pushing for progress on climate

As stated in our 2025 Climate action plan, we believe that the fund stands to benefit from an orderly transition towards global net zero emissions that fully addresses the risks associated with climate change. We expect company boards and management to have climate change strategies consistent with our climate change expectations.

We understand that the energy transition will unfold over decades, will differ across markets and industries, and will depend on boards and management teams making complex decisions about future physical, regulatory and technological scenarios. This requires engagement with companies over a long period and may lead us not to support overly prescriptive shareholder proposals. For example, we may oppose a proposal requiring a ban on financing of fossil fuels within a relatively short timeframe, as this may not be in the best interests of the company or the energy transition.

Nonetheless, we may escalate a concern and take action when we believe companies are materially misaligned with the aims of our climate change expectations.

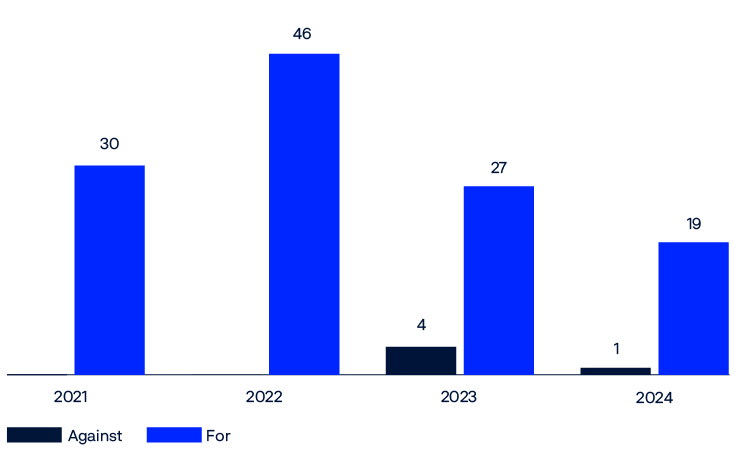

For the second year, we filed shareholder proposals relating to climate change. We filed proposals at three high-emitting US energy companies, requesting that they set an emission reduction target, on an intensity or absolute basis, covering operational (scope 1 and 2) emissions. After meetings with the companies, we withdrew two of the proposals following long and constructive dialogue that led to one company committing to increase public disclosure on the topic and the other providing clarity on the financial materiality of operational emissions.

We proceeded with the shareholder proposal at Kinder Morgan. After engaging in a multi-year dialogue with members of the management team to understand how they manage climate-related risks, we concluded that the company and its investors would benefit from setting scope 1 and 2 emissions targets that quantify the company’s efforts to reduce emissions. Our Chief Governance and Compliance Officer travelled to Houston, Texas, to present the shareholder proposal at Kinder Morgan’s annual general meeting. The proposal received approximately 31 percent support from the investor base. Members of the company’s management and board, who have a significant holding of 12.6 percent, did not recommend support for the proposal. In a meeting with management following the annual general meeting, the company committed to paying attention to climate-related risks.

We continued to vote on ‘say on climate’ proposals, where companies ask their shareholders to approve their climate plans, and supported the large majority.

Our support for ‘say-on-climate’ proposals

Appendix

|

Concern leading us to vote against companies (all topics) |

Percentage of companies opposed |

|

|---|---|---|

|

H1 2024 |

H1 2023 |

|

|

Combined chair/CEO |

7.4 |

7.3 |

|

Lack of board independence |

5.7 |

7.0 |

|

CEO pay |

5.2 |

5.6 |

|

Financial statements |

4.4 |

4.5 |

|

Changes to bylaws or charter |

3.9 |

2.7 |

|

Independence of main committees |

3.6 |

3.8 |

|

Board nomination and election |

2.9 |

2.9 |

|

Overcommitted board members |

2.8 |

3.7 |

|

Auditor |

2.3 |

2.5 |

|

Board gender diversity |

2.1 |

2.7 |

|

Holding the board accountable |

1.5 |

1.9 |

|

Anti-takeover measures |

1.3 |

1.6 |

|

Sustainability reporting |

1.3 |

1.3 |

|

Share issuance |

1.1 |

1.3 |

|

Related party transactions |

0.9 |

1.1 |

|

Merges, acquisitions and other corporate transactions |

0.2 |

0.3 |

|

Multiple share classes |

0.2 |

0.3 |

|

Meeting requirements |

0.2 |

0.1 |